PRESS FREEDOM IN TURKEY

Dimpool Analysis Team

TUGCE ERCETIN

30 April 2011

We all know that expressing our thoughts, ideas, and political perceptions are primary rights if we believe that we are living in a free country. However, in Turkey we cannot deny that there is still a lack of democracy and freedom of press. Fundamental rights and freedoms are not sufficiently protected by the government, as the Turkish public cannot express any opposing thoughts.

If some people still think that Turkey could be a model for Middle Eastern countries, I would suggest that those same people reconsider these thoughts. Consolidation of democracy is a difficult process but, on the other hand, it requires the people’s will for democracy. Citizens, journalists, analysts, and activists should raise their voices politically, even though individuals suffer from pressure regarding freedom of expression, particularly in the media.

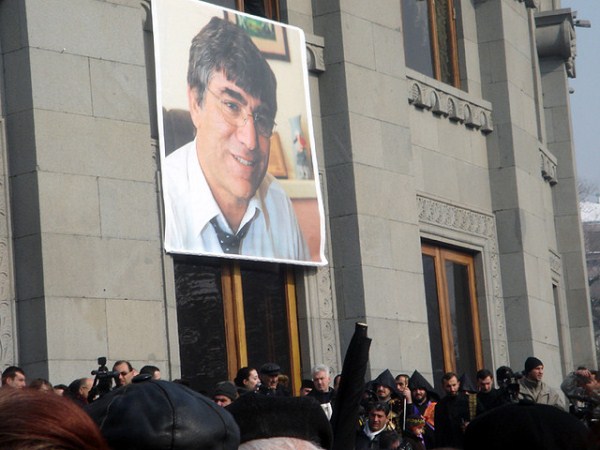

Hrant Dink

First of all, I would like to mention Hrant Dink, a Turkish-Armenian journalist who was assassinated in Turkey on January 19, 2007. Dink was known for being persecuted due to controversial Article 301 of the Turkish penal code, which makes it a crime to insult Turkish leaders and the Turkish nation. Although in the process of legal reforms parallel to EU accession Article 301 was amended, it was not enough to save Dink from conviction, because in his articles he had highlighted his Armenian identity. On April 6, 2004, he published an article in Agos Newspaper regarding Ataturk’s stepdaughter, Sabiha Gokcen, noting that she might have Armenian origins. Following his article, unidentified people in Istanbul Lieutenant Governor Erol Gungor’s office warned him. In addition, Turkish media moguls had started a campaign against him. On February 13, 2004, as a segment of his eight-part series of articles, he wrote: “The clean blood that will fill the vacuum of poisonous blood emerging through the lack of the “Turk” is present in the noble vain that will be established by the Armenian with Armenia.” This paragraph resulted in a new court case for Dink, but the real punishment for him was that the sympathizers of the ultra-nationalist Istanbul Ulku Ocaklari rallied in front of his workplace. Three years after those protests, Dink was assassinated in front of the Agos newspaper building. Even though main suspect Ogun Samast was captured only a day after Dink’s assassination, Turkish justice has still been unable to punish the murderer and the criminal group behind him.

Ozgur Gundem newspaper

Considering Turkey’s history of journalist assassinations, Dink’s murder was not an extraordinary event. On 14 April 1994, long before the AKP government took control, Ozgur Gundem, the newspaper whose 27 employees were murdered, was closed. According to Suleyman Demirel, the 9th President of the Republic of Turkey, those journalists were terrorists who were merely posing as journalists. The former president’s statements do not really matter much, as they were free young people who were trying to inform the public about the situation in Turkey. When Ozgur Gundem started publication on 30 May 1992, its employees and readers were not only attacked by the police forces but also by some civilians who expressed opposing ideas. This newspaper wanted to be a vocal opposition by trying to reflect Kurdish thoughts and news. The story of Ozgur Gundem was brought back to the agenda recently with the movie named “Press” and a reopening of the case with the same court.

Ahmet Şık and Nedim Sener

On March 3, 2011, a new day began for journalist Ahmet Şık with police officers in front of his door ringing his doorbell. On March 6, 2011, he was arrested and charged with being a member of the Ergenekon organization, at the same time his colleague Nedim Sener (author of a book on Dink’s murder) was being arrested. Şık was about to publish a book alleging that Fethullah Gulen Movement (FGH) sympathizers are in control of Turkey’s police force. Because journalists keep getting arrested to prevent their works from being published, at the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe (PACE) Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan compared Şık’s book to a bomb by stating “using a bomb is a crime, however it is also a crime to use the materials used in preparing a bomb.”

Conclusions

In a free country, you would not expect a knock on your door during the wee hours of the morning just because you expressed your opposing thoughts and ideas, but in Turkey nowadays it sounds completely ordinary since police officers raid journalists’ homes or printing houses in order to search and destroy even unpublished books. If Turkey cannot investigate it’s untouchable communities, it would mean that the Turkish public is surrounded by oppression and fear.

I would like to end my article with Hrant Dink’s dream:

a Turkey and a world

that is more free, more just,

more happy, more hopeful

for everyone

a Turkey and a world,

that is free from

discrimination, racism and violence

* Tugce Ercetin is a volunteer expert of Dimpool – Web Based Policy Center. Currently, she is an undergraduate student at Kadir Has University, department of international relations.

You might also want to read[srp srp_number_post_option=’5′ srp_widget_title=’ ‘ srp_thumbnail_wdg_height=’60’ srp_thumbnail_wdg_width=’60’ srp_include_option=’1266′ srp_thumbnail_option=’yes’ srp_content_post_option=’titleonly’] |